|

| HKU Press 2005 |

The year 2015 has seen the re-emergence of Hong Kong's Article 23 issue. It has been almost 12 years since the Hong Kong government withdrew its national security bill after a massive protest. Those events in 2003 were a defining moment in Hong Kong's post-1997 history and have contributed in significant ways to who and what we are now as a special administrative region of China.

The February 2009 passage of Macau's Article 23 legislation under very different conditions has added to the pressure on Hong Kong to re-introduce proposals. National security concerns were explicitly mentioned in the restrictive political reform decision of 31 August 2014 by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. In January 2015, a Hong Kong deputy to the National People's Congress, Mr Stanley Ng, advocated the application of China's national security law to Hong Kong pending the enactment of local legislation. Despite the obvious constitutional difficulties with such a proposal, it reflected a growing frustration in some quarters over the issue, especially after the Occupy Central protests in 2014. Rumours circulated that the next Chief Executive elected in 2017, whether by universal suffrage or not, will have the unenviable job of implementation.

The terms of Article 23 provide as follows (numbers added only to highlight the seven requirements):

The general view in government is that Article 23 is a political hot potato that gets many people angry and can destroy ministerial careers. Many in the public see the issue as a serious threat to civil liberties imposed by the Chinese Communist Party and should be avoided as long as possible if not forever. In this article, to mark the 10th anniversary our edited collection on Article 23 published by HKU Press, I present a different view, that implementing Article 23 is an opportunity for legislators (especially pan-democrat ones) and the Hong Kong and central governments to rebuild mutual trust that has been badly damaged as a result of the universal suffrage reform debate. People forget how close we were to passing the legislation in 2003 after the government made its major concessions at the final hour. Those concessions removed the most objectionable aspects of the proposals. The passage of time has also demonstrated the absence of need for some of the proposals, such as the proscription mechanism against local organisations. In the review below, I reconsider each of the Government's proposals for the seven requirements of Article 23, discuss their criticisms, and identify constructive steps forward. (Note: references are to pages in the HKU Press book.)

1. Treason

a. What law exists now?

Reflecting its English law origins, Part I of the Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) criminalises the offence of treason (s. 2) and other related offences, including treasonable offences (s. 3) and offences against the person of the sovereign (s. 5). There are also common law offences of misprision of treason and compounding treason.

b. What was proposed in 2003?

The Government proposed to repeal all treasonable offences (s. 3), abolish the two common law offences, and replace the existing s. 2 treason offences with the following new provision shown below. It was notable that the new offence would only apply to Chinese nationals, but secondary parties to the offence could be non-Chinese nationals.

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

The proposal was mostly well received, for it significantly narrowed the net of criminal liability from that cast by the existing offences, and it phrased the offence in modern language appropriate to the 'one country, two systems' constitutional framework. References: Chen, pp 97-9; Roach, pp. 124-5; Choy & Cullen, pp. 166-77.

d. Where do we go from here?

Probably not much more needs to be done. The reform should be welcomed as it is rights-friendly and does away with archaic legislative language and offence definitions that were potentially very broad. For example, under the current law, one commits a treasonable offence by publishing writing that manifests an intention to depose the Central People's Government, an offence punishable by life imprisonment (s. 3(1)(a)). Such act of publication alone would not be an offence under the proposed offence, which requires proof of actual membership in foreign armed forces at war with China, instigation of an invasion by such forces, or assistance to a public enemy at war with China.

2. Subversion

a. What law exists now?There is no offence under Hong Kong law known as subversion. Much of what would be expected from the Chinese law notion of subversion as a criminal offence is probably covered by the existing treason offences.

b. What was proposed in 2003?

The Government proposed the following new offence:

|

| HKU Conference - Nov 2002 |

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

There were three main criticisms of the proposal. The external elements of the offence ("disestablishing the basic system of the PRC", "overthrowing the CPG", and "intimidating the CPG") were too vague and uncertain. What precise acts or circumstances would constitute overthrowing the CPG? Who's to say when the CPG has been "intimidated"? The second criticism was directed at the broad definition of "serious criminal means", which included in sub-paragraphs (iv) and (v) non-violent means. After 2014's Occupy Central protests, people will be very concerned if peaceful civil disobedience falls afoul serious national security laws rather than only minor public order offences. The third criticism was directed at the vague notion of the criminal means "seriously endangering the stability of the PRC". What form of stability, e.g. economic, political, social, etc.? And at what point would there be "serious endangerment" of such stability? References: Fu, p. 90; Chen, pp 98-102; Roach, pp. 132, 135-9; Choy & Cullen, pp. 178-85; Weisenhaus, pp. 287-8.

d. Where do we go from here?

Government needs to go back to the drawing board. A clearer description of the prohibited de-stabilising circumstances needs to be provided. Macau's National Security Law (Art. 3(1)) does not have the "disestablish" limb but has the "overthrow" limb and another limb ("prevent or restrict its functions") that is potentially problematic. Two approaches are possible to addressing the "serious criminal means" problem. One is to drop sub-paragraphs (iv) and (v) or restrict them only to circumstances involving violence or threats to the safety of a person. The other approach, as advocated by Kent Roach, is to provide an exception for acts done "in the course of any advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action" (see the exception in the definition of terrorist act in the United Nations (Anti-Terrorism Measures) Ordinance (Cap. 575), s. 2(1)). References: Roach, pp. 138-9.

3. Secession

a. What law exists now?There is no offence under Hong Kong law known as secession.

b. What was proposed in 2003?

The Government proposed the following new offence:

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

The problems with "serious criminal means" and "seriously endangers" seen with the subversion offence are also present in this proposal. The critical element of withdrawing a part of the PRC from its sovereignty is also vague. One withdraws money from a bank account or withdraws oneself from a particular place but it is more difficult to imagine what it takes to withdraw a part of a country from its sovereignty. Another problem was with the meaning of the external element of "using force" as an alternative to "serious criminal means" - the full expression is "using force that seriously endangers the territorial integrity of the PRC". After Occupy, one will ask whether protesters barricading a main road preventing vehicle passage and inhibiting police enforcement action over several months will satisfy this element. Surely the purpose of the conduct will be determinative, yet the proposal is silent as whether the mens rea is one of intention to secede or mere recklessness as to the prohibited acts/consequences. References: Chen, pp. 98-102; Roach, pp. 129-131; Loper, pp. 205, 209-212, 216; Weisenhaus, p. 288.

d. Where do we go from here?

As with subversion, this is another proposal that needs further thought, clarification and perhaps elaboration. If "serious criminal means" is restricted to violence related activities or subject to an advocacy or protest exception then question whether it is still necessary to have the "using force" alternative. Given the potential punishment of life imprisonment, the offence needs to include the greater moral culpability requirement of 'intention to secede' from the PRC. The withdrawal element should be defined more clearly - perhaps by reference to conduct that precludes or frustrates the ability of the government to exercise its complete authority over a part of its territory. Reference can be made to Macau's National Security Law (Art. 2(1)) which refers to "acts to try to separate territory from the state or subject it to the sovereignty of another state".

4. Sedition

a. What law exists now?

Part II of the Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) provides for offences, procedures and police powers in relation to sedition. Section 9(1) provides a broad definition of "seditious intention"; s. 10 provides for offences based on acts done with a seditious intention including uttering seditious words and publishing seditious publications; s. 14 confers warrantless police powers to remove seditious publications; ss. 15 to 17 provides for offences in relation to unlawful oaths.

b. What was proposed in 2003?

Existing offences were to be replaced with more narrowly defined sedition offences and offences of handling seditious publications. Mere possession of seditious publications would not be an offence. The police power to remove seditious publications, the statutory definition of seditious intention, and the three provisions related to unlawful oaths were to be repealed.

The sedition offence would take two possible forms (s. 9A(1) - see below). The first was as an offence of inciting treason, subversion or secession, punishable up to life imprisonment. It would replace the common law offence of incitement in relation to those three crimes (s. 2D). It would be narrower than the common law offence because of the "likely to be induced" nexus requirement proposed in s. 9A(1A), reflecting principle six of the Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression and Access to Information (1996). The double inchoate offence of inciting sedition could not be charged (s. 9B). The second form was inciting others to engage in "violet public disorder that would seriously endanger the stability" of the PRC. The same "likely to be induced" nexus requirement applied. This offence was punishable up to seven years imprisonment.

The offences of handling seditious publications proposed in s. 9C (see below) were narrower than the existing offences because of the "likely to induce" nexus requirement and the express "intent to incite" mental element. However, the maximum punishment was to increase from three to seven years imprisonment and the limitation period for prosecution was extended from six months to two years.

Proposed s. 9D (see below) provided defences to the new sedition offences (ss. 9A & 9C) for legitimate expression providing constructive criticism of government practices and laws. These defences already exist under the current law (s. 9(2)).

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

The repeal of the old law was welcome, but there were still concerns with the new proposals. The late concession to include the "likely to be induced" requirement was able to address some concerns. However, the second form of the sedition offence suffered from the problem seen earlier with the vague expression "seriously endanger the stability" of the PRC. People will wonder if the protests and clashes seen during the 2014 Occupy events constitute "violent public disorder"? Even if so, most would say that it was not violent public disorder "that would seriously endanger the stability" of the PRC. But at point would it so endanger? Questions come back to this vague expression. Many also wanted to see the proposal for the seditious publication offences withdrawn, for fear that it could chill the publication and dissemination of legitimate political expression. References: Petersen, p. 45; Chen, pp. 104-6; Roach, pp. 127-9, 140-4; Loper, pp. 214-5; Fu, pp. 243-9; Weisenhaus, pp. 284-7.

d. Where do we go from here?

While the first proposed form of sedition is fine, serious consideration needs to be given to whether the second form of sedition is necessary. Incitement is a common law offence that can be charged in relation to most other violence related offence, so the ordinary criminal law will still be available. If it is kept, the element of "seriously endanger the stability" will need to be clarified. The Macau National Security Law (Art. 4(1)) does not have the second form; it has the added requirement that a person must "publicly and directly incite" treason, subversion or secession - this is a safeguard worth considering.

With seditious publications, existing offences and police powers are wide and fortunately have not been used to impact press freedom. With the narrower proposed offence that has safeguards in the express mental element of "intent to incite others" and the defences in s. 9D, the proposal on balance is probably justifiable. But note that the Macau National Security Law did not include an offence related to seditious publications.

5. Theft of State Secrets

a. What law exists now?

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

The Official Secrets Ordinance (Cap. 521) currently provides for several offences in relation to espionage (Part I) and protects a wide range of government information from unlawful disclosure (Part II).

b. What was proposed in 2003?

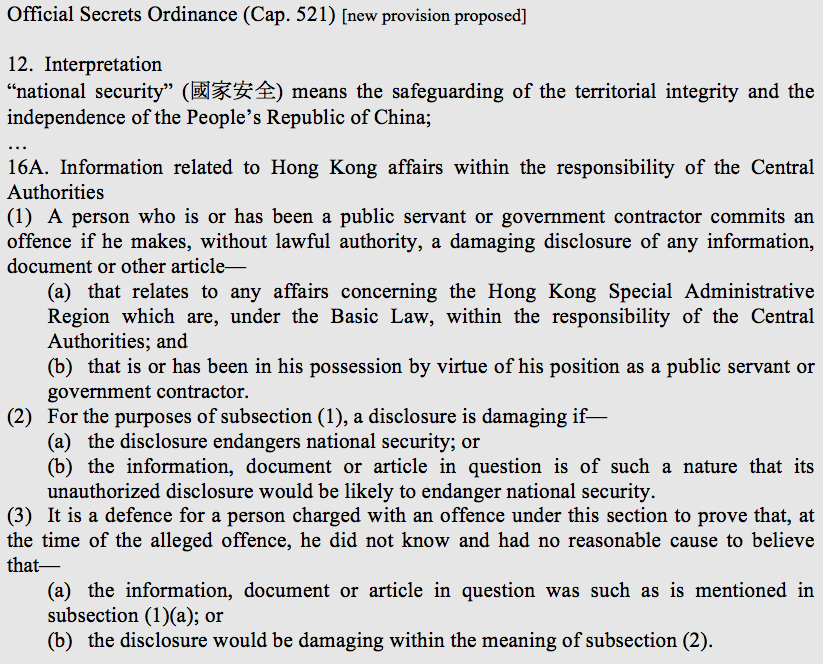

It was felt that there were two gaps in the existing legislative framework that needed to be filled. The first was the potential disclosure of information related to Hong Kong affairs within the responsibility of the Central Authorities (s. 16A - see below).

The second perceived gap was in relation to disclosing protected information obtained by specified illegal access, e.g. computer hacking, theft, bribery, burglary and bribery (s. 18 - see below). In the Post-Snowden era, close attention needs to be paid to the terms of this proposal.

In July 2003, a late concession was made to provide for a "public interest" defence to only the illegal access offence provision (s. 18(5B)).

|

| HKU Conference - June 2003 |

Criticisms were directed at a number of points. In relation to the proposed s. 16A offence, the scope of "affairs concerning the HKSAR which are, under the Basic Law, within the responsibility of the Central Authorities" was unclear. Did it refer only to matters of defence and foreign affairs or all matters relating to the Central Authorities under the Basic Law? It was said that "national security" was unclear in referring to "safeguarding the independence" of the PRC. The mental element was also problematic because a person could be convicted even if he genuinely did not know that he was making a damaging disclosure of protected information. Constitutional review of the reverse onus provision in s. 16A(3) would likely read it down to an evidential burden.

As for the s. 18 offence based on illegal access, there was a similar concern with basing liability on "having reasonable cause to believe" as it was still possible to convict someone who did not genuinely believe. Was it an anomaly that the new public interest defence was only to apply to the s. 18 offence and to none of the other offences of damaging disclosure? There were also criticisms of the narrow scope of the public interest defence. For example, it probably would not cover Edward Snowden's disclosures about the PRISM surveillance programme. Finally a prior publication defence was advocated. References: Petersen, p. 39; Chen, pp. 109-111; Roach, pp. 132-4; Loper, pp. 212-4; Chan, pp. 258-276; Weisenhaus, pp. 290-7.

d. Where do we go from here?As for the s. 18 offence based on illegal access, there was a similar concern with basing liability on "having reasonable cause to believe" as it was still possible to convict someone who did not genuinely believe. Was it an anomaly that the new public interest defence was only to apply to the s. 18 offence and to none of the other offences of damaging disclosure? There were also criticisms of the narrow scope of the public interest defence. For example, it probably would not cover Edward Snowden's disclosures about the PRISM surveillance programme. Finally a prior publication defence was advocated. References: Petersen, p. 39; Chen, pp. 109-111; Roach, pp. 132-4; Loper, pp. 212-4; Chan, pp. 258-276; Weisenhaus, pp. 290-7.

A enumerated list of the affairs within the responsibility of the Central Authorities should be provided. Consider also limiting the category of information to items that should be kept confidential (see s. 16(5)). The Macau National Security Law defines state secrets as information "that must be kept secret and are classified as such" (Art. 5(5)). The definition of "damaging disclosure" in s. 16A needs more thought. Reference to the more concrete ways in which this expression is defined in other sections may provide guidance (e.g. "disclosure causes damage to the work of...the security or intelligence services" (s. 14(2)(a)), "disclosure damages the capability of, or any part of, the armed forces to carry out their tasks" (s. 15(2)(a)), "endangers the safety of British nationals or Hong Kong permanent residents elsewhere" (s. 16(2)(a))). While "endangering the territorial integrity of the PRC" is probably fine but something more tangible than "endangering the independence of the PRC" is needed in drafting a workable concept of "national security". Attention needs to be paid to the fault element in both offences and whether having a subjective standard of recklessness (in place of the objective standards) will be sufficient, and without reversing the burden of proof. Finally, thorough consideration needs to be given to the scope and broader applicability of the public interest defence.

6. Prohibiting Foreign Political Organizations or Bodies from Conducting Political Activities in the Region &

7. Prohibiting Political Organizations or Bodies of the Region from Establishing Ties with Foreign Political Organizations or Bodies

a. What law exists now?

The Government conceded that the Societies Ordinance (Cap. 151), especially after its amendments in 1997, had already implemented the last two Article 23 requirements against foreign political organizations conducting political activities in Hong Kong and establishing ties with local political organizations (see ss. 5, 5A, 5D, 8; Consultation Document, p. 44).

b. What was proposed in 2003?

But, given the potential seriousness of national security risks, the Government felt it was necessary to have additional measures to deal with organizations that pose a risk to national security. It proposed a new executive proscription mechanism to blacklist certain local organizations (s. 8A). There were to be basic procedural requirements for proscription (s. 8B) and a right of appeal to the Court of First Instance (s. 8D). Originally, it was proposed that a local organization could be proscribed on three grounds: (1) it has an objective of engaging in treason, subversion, secession, sedition or spying; (2) it has committed or is attempting to commit treason, subversion, secession, sedition or spying; (3) it is subordinate to a mainland organization which has been prohibited on security grounds by the PRC. As a late concession, the third ground for proscription was withdrawn. What remained of the proposed proscription power is shown below:

There were to be new offences for participating in or aiding a proscribed organization (s. 8C) and existing offences relating to unlawful societies (ss. 21, 22, 23) were to be extended to proscribed organizations. The defences seen in s. 8C(1A) were included as a late concession.

c. What did commentators think of the proposals?

The greatest concern was with the third ground for proscription as it was seen as a "connecting door" (p 309) allowing mainland authorities to silence undesirable groups and individuals in Hong Kong. Even with the withdrawal of this controversial ground, there were still concerns with the potential criminal liability of persons involved or engaging with proscribed organisations. The defences in s. 8C(2) & (3) reversed the burden of proof on the defendant and thus were constitutionally liable to be read down as evidential burdens. They also required defendants to meet objective standards of ignorance and prevention. There were also concerns with ensuring fairness in the proscription appeal mechanism. References: Petersen, p. 26; Chen, pp. 111-115; Harris, Ma & Fung, pp. 305-330; Feng, pp. 331-61.

d. Where do we go from here?

With the withdrawal of the third ground for proscription, it must seriously be considered whether the proscription mechanism is still needed and should be proposed. There are a number of reasons now for not adopting this controversial mechanism that impinges upon freedoms of association, expression and commerce. First, it is not required for implementation of Article 23. Second, the Macau National Security Law did not include it, which Godinho said was the "most positive aspect" of the Macau bill (p. 18). Third, the idea only arose because it was used in anti-terrorism legislation which had been enacted in 2002 in response to UN Security Council requirements after 11 September 2001 (from work done by the same policy team). Experience has now shown that blacklisting terrorists and terrorist groups has many difficulties, e.g. problematic legal issues, interference with individual rights, and detrimental impact on peace-building (see 2015 report by the International State Crime Initiative, Queen Mary School of Law). Fourth, the blacklisting mechanism available under the United Nations (Anti-Terrorism Measures) Ordinance (Cap. 525) will likely to be able to cover most if not all of the cases for which resort to the proposed proscription mechanism would be needed. Fifth, no groups have appeared or formed that would lead the public to call for their proscription on national security grounds.

Conclusion

In this review I assume that in any future Article 23 exercise the government would not seek to advance anything more controversial than their final set of proposals in 2003. Looking only at the substance of those proposals, the disagreement was not great. The proposals on treason and sedition were already near consensus. They are the least controversial, and bearing in mind the existing laws that stand to be repealed, the proposals should generally be welcomed. Dropping the seditious publication offence proposal (consistent with the Macau law) would surely leverage more support from the press and media community. If Government can forgo the proscription mechanism, then this will settle (more or less) four of the seven Article 23 requirements. It leaves subversion, secession and state secrets. The difficulties here are more to do with legislative drafting than with differences in policy or principle. Building on the work done so far, a working group of relevant legal and policy experts should be able to construct a set of carefully balanced proposals (informed by comparative law and international standards, such as the Johannesburg Principles) that are likely to be acceptable by all parties.

I draw the conclusion that a consensus on the details of implementing Article 23 is possible if the stakeholders are prepared to put politics aside. Indeed reaching such a consensus would be a sign of a new plateau of trust from which further progress could be made, such as on matters of political reform. Rather than fearing and loathing the Article 23 issue, Hong Kong legislators should see it as an opportunity for rebuilding trust with the Hong Kong and mainland governments. Written by Simon NM Young.

Further Reading

Buddle, Cliff, "Hong Kong's Article 23 obligations are already in our legal armoury", South China Morning Post, 29 January 2015.

Cheung, Alvin YH, A Spectre Resurfaces: Chinese National Security Legislation and Hong Kong, Int’l J. Const. L. Blog, 11 February 2015.

Cheung, Alvin YH, A Spectre Resurfaces: Chinese National Security Legislation and Hong Kong, Int’l J. Const. L. Blog, 11 February 2015.

Chung, Francis HC, "Navigation between Autonomy and Authority: Some Suggestions on the Future Legislation under Article 23" (2013) 7 Hong Kong Journal of Legal Studies 1.

Fu Hualing, Carole J Petersen and Simon NM Young (eds), National Security and Fundamental Freedoms: Hong Kong's Article 23 Under Scrutiny (HKU Press 2005).

Fu Hualing & Richard Cullen, "National Security" in J Chan & CL Lim (eds), Law of the Hong Kong Constitution (Sweet & Maxwell 2011) ch 6.

Godinho, Jorge, "The regulation of article 23 of the Macau Basic Law: A commentary of the draft law on the protection of State security", 28 November 2008, available on SSRN.

Hu, Bob, "The Future of Article 23" (2011) 41 Hong Kong Law Journal 431.

Kellogg, Tom, "Legislating Rights: Basic Law Article 23, National Security, and Human Rights in Hong Kong" (2004) 17 Columbia Journal of Asian Law 307.

Lo, PY, The Hong Kong Basic Law (LexisNexis 2011) ch II.

Young, Simon NM, "Security Laws for Hong Kong" in VV Ramraj, M Hor, K Roach & G Williams (eds), Global Anti-Terrorism Law and Policy, 2nd ed (Cambridge University Press, 2012) ch 15.

Article 23 will kill Hong Kong's one country two systems the fastest. In fact, China is smart to realize through the November 2016 Interpretation of Article 104 of the Basic Law to circumvent this controversial enactment of Article 23 to achieve the same political goal. One country two systems only exists in name now. No wonder the Economist called Hong Kong the New Tibet. I pity Hong Kong.

ReplyDelete